Having written about video games’ potential to aid in mental wellness, I’ve come to keenly understand and have a deep appreciation for gaming’s power to heal minds and souls. But what about actual depictions of mental health in games?

Several games have delved into mental health and mental illness. One such game is a recent indie darling, lauded by fans and critics alike for its relatable, nuanced storytelling and tough-as-nails (yet still surprisingly accessible) platforming.

I’m talking, of course, about Extremely OK Games (the studio formerly known as Matt Makes Games)‘s 2018 hit, Celeste.

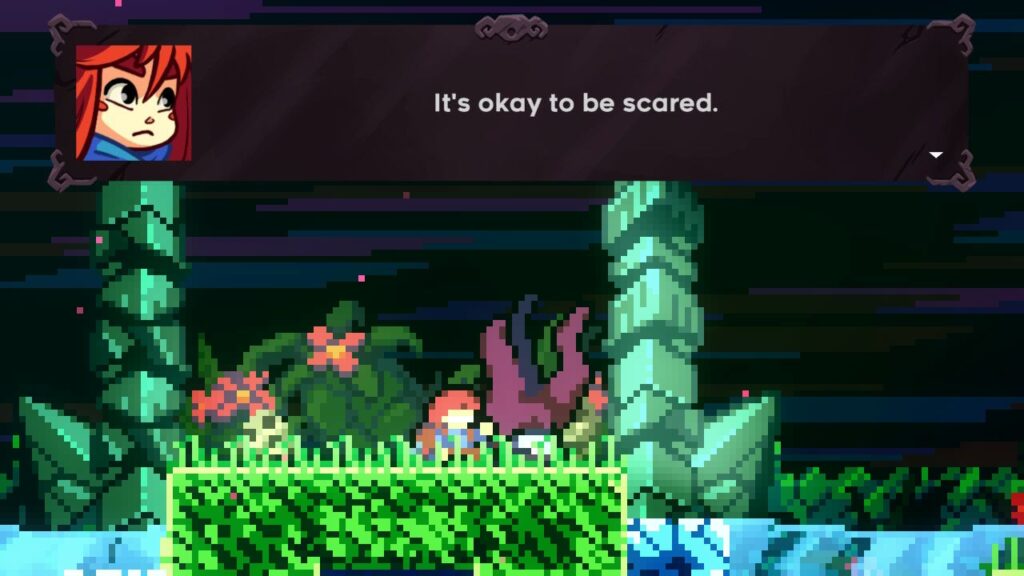

The game features charming pixel art, a moody and catchy soundtrack, highly challenging gameplay tempered by robust and non-judgmental assist settings, and likable characters who go through internal struggles that everyone grapples with at some point.

The characters in Celeste are delightful from start to finish, and the game brilliantly captures the complexity of each characters‘ mental state—from Madeline’s struggles with anxiety to the tragedy of Mr. Oshiro’s tormented soul. The game is also packed with visual symbols and metaphors for anxiety, loss, the shadow self, and other psychological concepts.

To get a deeper look at each character’s psyches and how they address (or don’t address) their issues, I spoke with Larisa Garski, LMFT, a gamer, podcaster, and mental health practitioner that specializes in working with geeks, gamers, and others outside the mainstream.

Turns out there is so much to unpack with Celeste that we couldn’t cover all of it—the feather, or the phone call, for example—but it was nonetheless an illuminating conversation which we hope will give you an even deeper appreciation for this indie classic.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

SPOILER ALERT: This article contains major spoilers for Celeste. If you haven’t played through The Game and its DLC, and wish to discover the story and ending for yourself, close this tab and come back once you’re finished.

Jay Rooney: So, Celeste! Have you played through the DLC yet, or just through the main game?

Larisa Garski: I’ve just played through the main game, and I have started the DLC, but I’m very early in it. But at this point, feel free to give me spoilers. I’ve looked at it a little bit in preparation for the interview today, but at some point, I was like, “Oh man, I’m not going to be able to make it through before we chat.”

JR: Well, getting to the point where you can even start the DLC means you’ve pretty much finished the rest of the game. That could take a very long time, especially if you’re the type of person that doesn’t use assist mode.

LG: I have to say this is the first game I’ve played in a couple of years where I really could feel the fact that I came to gaming as an adult. I don’t have that kind of technical fine motor control, the dexterity to be technically skilled in the way that this game requires.

JR: I didn’t mind using assist mode because my whole thing was I just wanted to see the story through, and in that sense, I have no regrets. Assist mode, it never feels judgmental when you turn it on. So that was a nice design choice that I really appreciated.

Madeline, the Mountain, and Change

LG: I also really appreciated, oddly enough, how challenging the game was from a technical perspective because I thought it did a great job of mirroring the way it’s so hard to enact change in our life.

JR: I hadn’t thought of it that way.

LG: Yeah, I thought of it because at the time, I was working clinically with quite a few folks and we were all looking the trans-theoretical model of change, which is six steps of change broken down into all the different levels. And I like to use that with clients because it helps them appreciate why it can take so long to change.

[CONT’D]

The Six Stages of the Trans-Theoretical Model of Change

- Pre-Contemplation: Person has not bought into change and is just beginning to think about possibly looking into change, more likely getting this feedback from others.

- Contemplation: The “getting ready” phase. Person is actively thinking about what it would take to make this change.

- Preparation: Person is actively getting pieces together: researching, seeking input/recommendations, figuring out logistics and finances, etc.

- Action: Person starts trying to get a sense of not just what they want to change, but how they want to change it, then enacts this change.

- Maintenance: Person works on how to maintain the action taken, how to integrate it, what support they need to continue on their new path.

- Termination: Person closes out, feels like they’ve gotten what they need, feels like they have zero to minimal attraction for previous negative behavior or coping strategies.

Progress in this model is not usually linear; regression and re-attempts are common, expected, and normal parts of change.

LG: And that’s the game, too. It shows it’s such a long process to integrate things, new behaviors, even once you have the awareness. I appreciated that about the game.

JR: So, as far as Madeline’s journey, how does the game portray [change] visually?

LG: The mountain, right? From a distance, you have this sense of, “well, I need to go up and I need to reach the top.“ But then, within the process of the game, as she’s going through the different levels, you see that sometimes you have to go down to go up. This also brings in that idea that regression is part of change, that sometimes we have to go back and revisit old ways of being to learn about ourselves. That can be an important part of how we figure out how to maintain the change that we want to see or be in our lives.

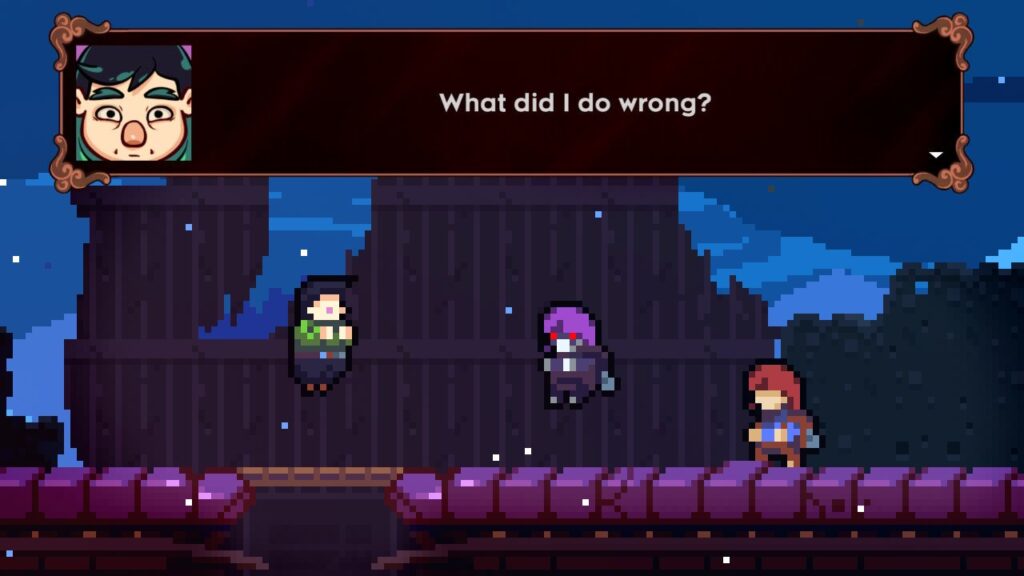

Same with Badeline and Madeline, the way they balance each other. And they argue and move back and forth between thinking, “do we want to climb the mountain, are we ready to climb the mountain?” And Madeline will get to different points in the game and say, “no, yes, this is what we’re doing. No more arguing, we’re doing this.”

They do a great job of showing the cyclical nature of it. When Madeline comes to the mountain, it’s because she doesn’t want to feel panic anymore, she doesn’t want to feel depressed anymore. Yet, not all of her has totally bought into all of that, not all of her believes that they can do it.

Regression is part of change.

JR: It’s also interesting that even after they summit the mountain, the next time you see them is at the start of the new DLC, after the old lady has passed. Madeline is trying to process that loss, and she’s having trouble letting go. And then Badeline finally just says, “alright, well I can’t help you with this. You want to do it, go nuts.”

And so she leaves, and at that moment, you lose the ability to do the second mid-air dash that you acquired after they reconciled. That was an interesting visual metaphor for the fact that accomplishing goals and growth is not the end of it; you don’t magically become this changed person, you don’t permanently “level up.” It’s an ongoing thing. That was a neat way to portray that.

LG: Yes, the video game speaks to that idea is that change is such an ongoing process, and you’re never really done. As soon as you think you’re done, there’s another mountain to climb, and there’s another part to be explored.

Even as Madeline and Badeline end the main game very much working together and in concert, they will come out of alignment again. Then they will have to figure out new ways to work together, in part because their external environment does continue to change, so that brings up new things for them to face.

JR: It’s a pretty big contrast to their interactions while they were working together to summit the mountain after they reconciled. Like how as you finish one section and bolt to the next, they always have some dialogue. And the dialogue shifts as they start to become more comfortable with each other.

But then, in the DLC, they’re arguing and fighting again. It’s all a process, like everything else in life. I liked seeing the devs take that route instead of saying “happily ever after” and leaving it at that.

Badeline, Jung and “The Shadow Self”

JR: And speaking of Badeline, that brings us to the shadow self. Let’s talk more about that whole Jungian archetype.

LG: I love that you brought up Jung because there is so much of that there. Including this idea that the shadow archetypes are one of the first tropes that live in the collective unconscious, which we all have access to via our individual unconscious.

The shadow Jung always talked about was the first archetype that we have to “do battle” with, and each person’s individual shadow represents parts of themselves that they’ve rejected. Maybe they’ve rejected them because the society or culture in which they’ve been raised has taught them that these parts of themselves are no good, or they’re shameful. Maybe they’ve rejected these parts of themselves because they feel like these tendencies are getting them into trouble.

But for a person to really become a fully integrated or individuated self, which is the goal of Jungian psychoanalysis, you have to face the shadow. You have to do battle with your shadow and really engage with it.

And Badeline is not only “shadowy” in the way they visually depict her, but she’s also this part of Madeline that Madeline doesn’t want to be with, she doesn’t want to be with her panicked parts. She doesn’t want to be with those parts that she’s unable to process.

She initially very much wants to sever the things she’s identified as problematic parts of herself, as if it were some sort of tumor that she can remove.

JR: Then when she tries to do that, Badeline gets really pissed, and knocks her all the way down the mountain. It’s depicting how the more you abort, or try to put under, or cut ties with your shadow, then the stronger it pushes back.

LG: Yeah, the more you repress it. A version of that is something I’ll also talk about with folks in terms of emotion.

One of your emotions’ functions is that they work as messengers. And so as you try to repress your emotions, another messenger is sent, and another, until finally, you feel sadness (for example) that has become so enormous, so intense that it breaks down the wall of your psyche because you haven’t been listening to it.

But maybe, if you had paid attention to that first sadness messenger when it got sent, the situation wouldn’t have gotten to that place.

JR: Usually, when I see the shadow self archetype being portrayed visually, or as an external being, it’s framed as you battling with him, her, or it.

You see this with Dark Link. And then here as well—the real climax of the story wasn’t when Madeline was about to summit the mountain, it was her trying to get to Badeline, who just kept running away.

It’s a struggle. But at the same time, trying to defeat your shadow self just feeds into it and is counterproductive. What do you think the difference is between “battling” your shadow self and pushing it away?

LG: “Battling” with it entails engaging with it. If you’re pushing something away, you don’t even have to identify it, to name it. As soon as you feel that discomfort, as soon as you feel panic, as soon as you feel that downward spiral of mood, you can just push it away. You don’t need to bother figuring out if it’s sadness, grief, loss, or exhaustion. You can just repress it and put it away.

But if you’re battling with something, if you’re battling with a feeling—like when Madeline is battling with Badeline, or Link is battling with Dark Link—you have to look at your shadow. And you have to be able to identify it as your shadow. And I love that you brought up how near the end, Madeline is actually chasing her shadow.

JR: More like a reckoning, then. Got it.

In order to become that fully integrated self, you have to face the shadow.

LG: Jung was really… I’m going to out myself a little bit, but I think that he was sometimes a bit obtuse in the way that he wrote about things.

I think partly as a result of that, he would talk about battling with your shadow, but we’d take that to mean a literal battle, as if the self has to defeat the shadow and win. And what I understand Jung to be saying is that you need to engage, and it’s going to feel like a conflict, but ultimately it’s that coming together.

So I loved Madeline insisting “no, I’m going to keep chasing you.” So it’s not like she’s fighting with her shadow with fists or swords, Link-style. She’s chasing after her and insisting, “no, I feel you. I recognize you. I name you. I want to work with you. Come back. Come talk to me. Let’s figure this out.”

And at no point, well, I suppose that Badeline goes away sometimes, but the game maintains that idea that these two are staying together, just connecting in different ways.

Which is in contrast to Link, where you defeat Dark Link and then Link gets the hookshot and moves on, which is great, but it’s still that idea that the shadow is sublimated or beaten into submission.

[Celeste] takes a different interpretation. I don’t feel I see it as often, and I appreciate it.

JR: Right, because Madeline did try to sublimate Badeline, and it didn’t turn out well.

LG: Yes. And Badeline even expresses [after reconciling] the fear that you’re going to leave her again.

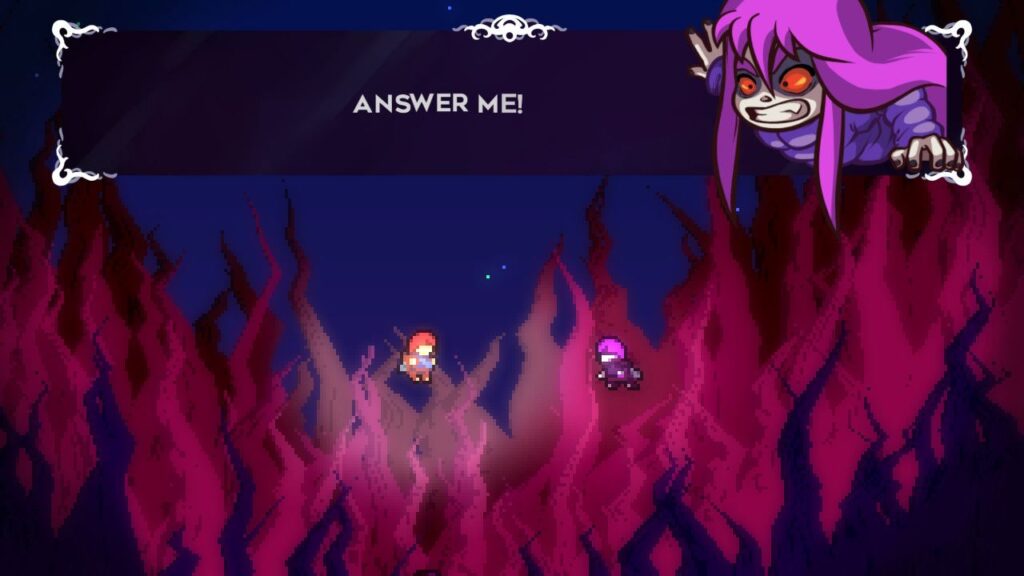

There’s that scene earlier, where the first time she says this, Badeline is angry and says, “you think you can just leave me behind. You think you’re above me.” And she’s coming more from that place of rage.

But when they’re working together and starting to trust each other a little more, or at least be a bit more open with each other, Badeline comes from a different place—a less aggressive and more sad or worried place of “are you going to leave me again? I don’t want you to leave me.”

Celeste takes a different interpretation to engaging the shadow self that I don’t feel I see as often.

JR: The way they portrayed Badeline’s rage visually too, with the pink tentacle things, and she leaps out of her frame, it made me jump a bit, like “whoa!” Man, I just love the visual symbolism in this game.

LG: Yeah, almost like breaking the fourth wall. I remember when I played it, I played it at night; it also made me jump.

JR: And the characters are very expressive too, with thir faces as they’re talking and even their talking voices that go “meh meh meh meh meh.” But surprisingly emotive. I thought it was all very well done.

LG: I completely agree. I didn’t think about this until you mimicked the voices, because they’re not speaking in words we can understand. But I realized it reminds me of Midna [from Twilight Princess], who also is speaking in words that we can’t fully understand but because of the inflection of it, there is so much nuance in that voice acting.

And I agree that there is so much expression in the way that Madeline does her gibberish, or Badeline does it, and the different tones of voice.

Theo, Selfies, and the Collective Unconscious

JR: Let’s recap a bit: at which points in the game does [Badeline] pop out? The first time was when she popped out of the mirror.

But then, the other big time she pops up is in the temple of mirrors, when Madeline gets sucked into this twisted nightmare world that’s supposed to be a reflection of herself. I’m curious what you see, what the visual symbolism there is.

LG: Well, I suppose from a Jungian perspective, that would have been Madeline crossing over into not just her unconscious, but the collective unconscious. And, am I remembering it right, is the mirror temple where she finds Theo again?

JR: Yeah, he’s trapped in that crystal thing.

LG: He’s trapped in the crystal thing, and he makes some comment about the fishy eyes, those eyes that swim around, that he thinks those are his.

JR: I remember. To paraphrase, Madeline said something like, “oh, you must think I’m horrible now, you must not want to see this side of me,” and Theo responds, “Madeline, this is not just a reflection of you, it’s a reflection of me, too.”

LG: Yeah. So, to me, from a Jungian perspective, I think that confirms that Madeline isn’t just in her own unconscious, she’s in the collective unconscious, which is where she could do things like bump into Theo and his Theo’s shadowy parts, and engage with them.

JR: And Theo was kind of trapped in that crystal cocoon, or whatever it was, and this just occurred to me: Theo is, we get the impression that he’s a very carefree, free-spirited individual, and then here in this situation he’s trapped. It’s the opposite of being free.

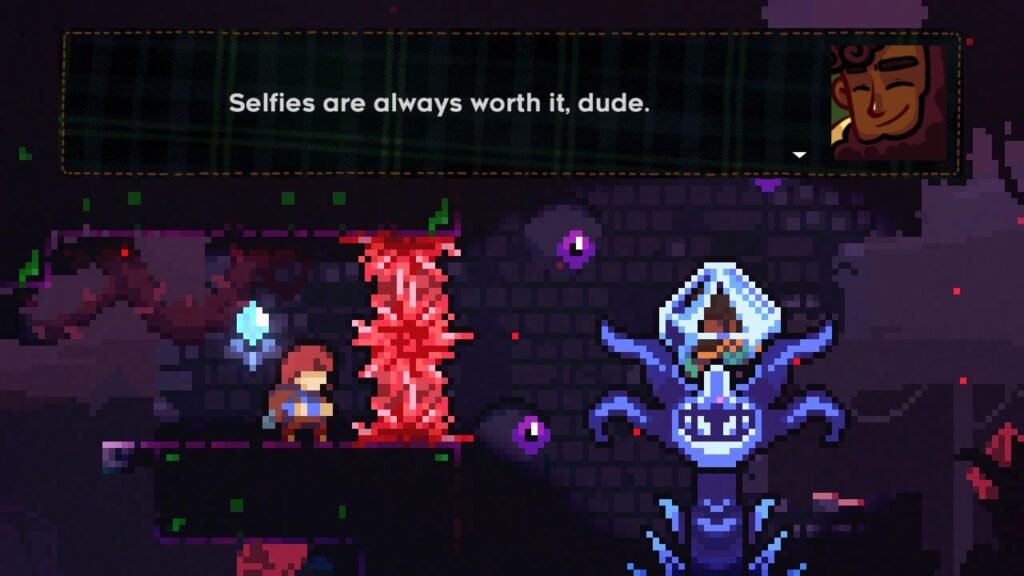

LG: It is, and actually I didn’t think of it until you said it just now, but I’m thinking about how Theo throughout the game is so into selfies.

Initially, it’s presented as because he’s so chill and confident, and at first Madeline makes a more self-disparaging comment about how, “oh, I’m not comfortable with it. I don’t feel comfortable being seen in that way.” And I remember while playing the game through, my judgment was Theo is comfortable. Theo’s maybe worked through his stuff.

Yet, when you get into the mirror temple, you see that it’s a little more nuanced than that. Maybe at times, Theo feels trapped by his practice of selfies. Maybe there’s more at play for him with wanting to be seen. Maybe there’s a shadow there for him, too.

JR: This brings us to what’s personally my favorite part of the game: the campfire.

LG: Yes. There’s a way that Madeline and Theo deeply connect, especially when they get out of the temple and are sitting around that campfire.

They’re able to be more vulnerable with each other and connect in a more profound way, having not just gone through this challenging experience but also having seen each other’s shadows. They can each, for each other, attempt to reflect back and offer “this part of you is not so awful.”

JR: That’s a good point. That whole scene by the campfire was very well done. Pretty much like everything Madeline said about dealing with depression and anxiety, I have either thought or said at some point—many times—in my life. They nailed that.

LG: Yeah, I agree—as a clinician, and as a person who, at different points in my life has struggled with both.

The Ballad of Mr. Oshiro

JR: Speaking of another very anxious character… tell me more about Mr. Oshiro.

LG: I feel so… (sighs) Mr. Oshiro just really tugs at my heartstrings for quite a few reasons. The big one is that he is so trapped. Do I remember correctly, I read him as a ghost—he is a ghost, right?

JR: Yeah, he is.

LG: Yeah, he goes back and forth and talks to himself in a very similar way that Madeline talks to Badeline. Part of what made it challenging for me as a person to see Mr. Oshiro, even at the ending, is that it feels like Mr. Oshiro never quite integrated with his shadow self.

He’s stuck and trapped. Literally! Architecturally, in the game, he’s between two worlds—the world of the living and the world of death or the beyond. And from the sense of a change model, he’s just trapped between contemplation and action, and he can’t commit to either. So he has no peace. He has no contentment. He’s just locked in this forever battle.

folks who need therapy and would benefit from it so much, are sometimes the least likely to go.

JR: Right. Similarly, there was a neat little reveal. Throughout the whole chapter there’s this kind of surface that’s kind of fuzzy, but if you linger too long, this weird red and black blob will pop up, which damages you so you can’t sit still too long.

And then, towards the end of the chapter, Mr. Oshiro’s having this dialogue with himself and then more of those blobs pop out. Those blobs represent all those years of suffering, just piled up, all over the hotel. He’s a tragic figure, for sure.

LG: He really is. My husband always teases me whenever I play games—and I don’t play many games with tragic characters—but I start to psychoanalyze them, almost as if they were real.

He’s like, “Larisa, you can’t do therapy with Mr. Oshiro, okay?” If you want to have that [therapeutic] experience with an avatar, you can have it with Madeline, but you’re not going to be able to do so with Mr. Oshiro. But he needs it the most.

JR: That’s sad.

LG: Yeah. And you notice that the folks who need therapy and would benefit from it so much, are sometimes the least likely to go.

The Old Lady: Every Hero’s Grandma

JR: The old lady. She’s a hoot.

LG: Isn’t she? Totally, that’s the perfect word for her. She’s a total hoot.

JR: Tell me more about Granny. What do you like about her?

LG: Granny is such a perfect iteration of the helper or the guide on the hero’s journey. I can’t believe we’re this far into the conversation, and I’ve yet to mention the hero’s journey!

So, Joseph Campbell, of the One Myth, he based a lot of his early work on things that Jung himself did. That idea of how, in every culture, we’re just retelling the same story in different variations.

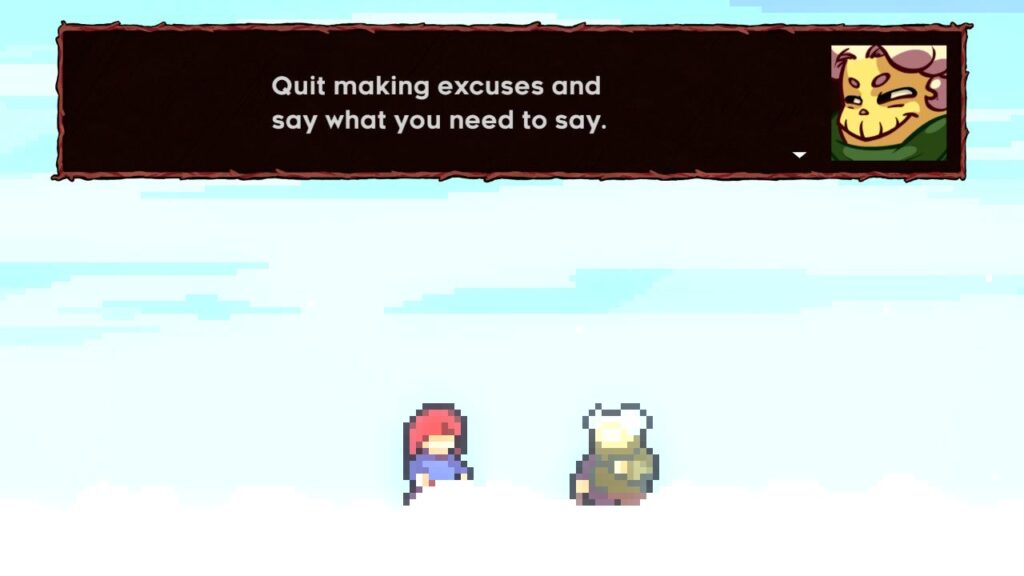

And Granny is very much the archetype of the crone, or the “old wise woman” or “old wise man” who often is rude to you and just seems really strange and abrasive and sometimes tells you the opposite of what she wants you to do.

I love how almost every step of the way she’s trying to convince Madeline, “you can’t do this. You should just turn back and go home.”

Of course, she’s doing this very purposefully. She wants to challenge Madeline and get that ire up in her and have Madeline get back up and insist and argue that “no, I will do this, I’m not backing down.”

They do a good job of having Granny pop up at key times in scenes when Madeline might be wavering. Granny’s there to do spur her on and make sure she keeps climbing.

In order for a butterfly to make it out of its cocoon, it has to really struggle.

JR: It’s funny too, because you’re right; usually she’s all, “oh, turn back, you can’t do this” until that point in which Madeline really has given up and is telling her, “you were right, I can’t do this.”

And then Granny goes right back and says “oh that’s a shame, for a while there I thought you might actually have made it!”

LG: Yeah, she’s such a sass. And wasn’t it Granny’s idea that Madeline work with her shadow?

JR: Totally. She said, “you know, why don’t you just talk to her?”

LG: I love that.

JR: Yeah, that’s deep.

LG: It really is. And Granny is so great, in that Granny shows that she is a healer. She is working as a guide, and she waits to give Madeline the key until she thinks that Madeline is ready.

As a therapist, that resonated with me because sometimes I get folks who come in for an intake, and by the end of that initial intake, I feel like I have a pretty clear sense of what they need and where we’re going. And yet, it’s not going to be therapeutically impactful for me to tell them what that is.

A really good friend of mine always loves to use the example of butterflies. For a butterfly to make it out of its cocoon, it has to struggle. And if you cut the cocoon so that the butterfly comes out too early, it dies—because it needed to struggle to build up its strength so that when it makes it out, its ready and can fly.

And there is some of that to therapy too. It’s not going to be helpful to do it for the client. You can help them and support them, but ultimately, they have to take the initiative. They have to climb the mountain on their own.

JR: Mind = Blown

Final Thoughts

JR: So, just to wrap up here. I was wondering if you had any general thoughts or advice on these themes of facing your shadow self, or dealing with feelings that make you uncomfortable, or overcoming huge challenges, or anything else that you would like to impart on our readers?

LG: That’s a good question. The first thing that comes to mind is knowing that it’s normal to be afraid.

I hear this a lot from folks that I work with—sometimes it’s self-consciousness, sometimes it’s downright guilt or shame, or feeling ashamed that it’s so hard, feeling ashamed that it’s frightening to face the shadow.

And yet, part of what we know from both Jung and Joseph Campbell is that you should be afraid.

It’s frightening to face your shadow. And frankly, if you feel afraid, that’s a good sign, ironically enough. It means that you’ve faced your shadow. It means your shadow is there in front of you. It should be overwhelming, and it should feel frightening at times. That’s okay.

It’s also okay to not want to deal with your shadow sometimes. The game does a great job of showing this—Madeline gets breaks, gets reprieves in the form of the disengagement that she has with her shadow.

It’s normal to be afraid.

JR: How about when it comes to sharing your struggle, or struggles, with others?

LG: It can be a really rewarding experience to share your journey with someone else, as long as you feel safe and feel the person you’re sharing with is a safe person.

Share your completed journey with your shadow—or your present journey with your shadow—with a person that you trust. It could be with a therapist, or even better, with a friend—like what Madeline does with Theo. Because then you get this kind of bidirectional validation that can be so very healing.

The technical term for it would be an “emotionally corrective experience,“ but you don’t have to write that down.

Larisa Garski is Clinical Director at Empowered Therapy, where she specializes in geek-focused narrative therapy, anxiety/depression treatment, relationship therapy, couples therapy, co-parenting counseling, and family therapy. She also co-hosts Starship Therapise, a podcast that covers different therapeutic concepts through the lens of fandom, and writes about psychology and gaming.

If you are feeling hopeless or going through a mental health crisis, you are not alone. Please call the Treatment Referral Hotline at 1-877-SAMHSA7 (1-877-726-4727) to get connected with resources. If you feel you are in danger of harming yourself, please call 911 or the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).